Ecosystem services (ES) may be defined as the human benefits generated by nature, such as forest, fauna, water, soil, or minerals, the latter being the stock of renewable and non-renewable resources that, using economic terminology, can also be identified as natural capital [1]. ES are drivers of social wellbeing emerging through their interaction with human and social capitals [2]. For instance, the contribution to human wellbeing derived from forestry and agriculture ecosystems requires human labor energy, and capital (machinery) input to convert them in societal benefits (e.g., crops and timber) [1:1].

A recent assessment carried out at the EU scale has defined and mapped a set of ES such as crops, pollination, timber, recreation, carbon sequestration, flood regulation, water purification and soil retention [3]. Limited attention has been given in the economic literature to soil erosion, water supply and regulation following wildfire events [3:1] [4]. Conversely, ecological values such as biodiversity, have been considered in the wildfire economic literature and monetised by eliciting the willingness to pay for its use value (e.g., wildlife watching) or non-use value, such as the existence value [5] [6]. Biodiversity can also be valued by its optional value, referring to the potential benefits generated by the protection of living beings because of their future bioprospecting use, such as for the production of drugs or new materials [7]. Provisioning services of forest ecosystems, such as timber and mushrooms, are usually considered in economic impact valuation or welfare analysis (cost benefit analysis) because they have a market price [8].

In terms of vulnerability, the ES most commonly affected by fire are timber supply, carbon sequestration and storage, pastures, hunting, mushrooms collection and recreation [9]. The value of those services can be either provided in biophysical units or in monetary terms. The latter can be obtained by adopting the total economic value (TEV) framework [10] [11] in combination with a “cascade model” that shows the relationships (for simplicity assumed linear) between the stock of natural capital (e.g., forest), the underpinning processes generating ecosystem services (e.g., woodland biomass, flood protection, carbon sequestration), and the benefits that contribute to human wellbeing (timber, non-timber forest products, health, safety, recreation and other cultural values, etc.) [12]. Regulating services like carbon sequestration can be the object of an ample range of values according to the methods used, fluctuating from the social cost of carbon, the price generated in the carbon market, and the marginal abatement cost of the national technology used to achieve a specific target of carbon reduction [13] [14]. Recreational values are a measure of welfare analysed by preferences for natural areas, parks, and species using travel cost methods [13:1] [15], and integrated with stated preferences, based on contingent valuation methods to assess the expected changes in number of recreationists under different fire scenarios [15:1] [16] [17] [18]. Landscape has also received attention with analysis of monetary values measuring quality [19], resilience to wildfire intensity [20] and loss of multiple values carried out by integrating the analysis of stated preference (contingent valuation method) [19:1] and burn probability [21].

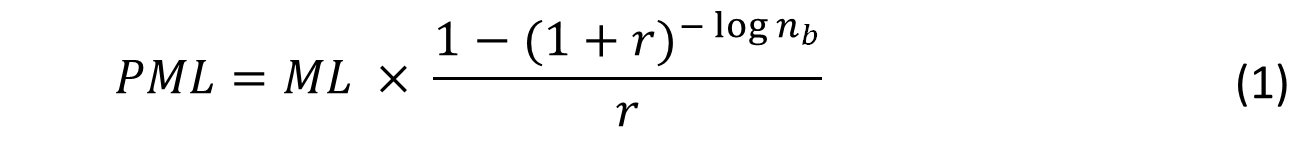

In all these studies the goal has been measuring the net value change or, in other terms, the lost benefits of the pristine environment net of the regeneration caused by forest recovery [20:1] [22] [23]. The goal is estimating the net value change of the asset, that is, the difference between its pre-fire value and the estimated post-fire value (assuming a certain fire severity level) and integrating the current losses incurred throughout the time until the full recovery of that asset is obtained. This has been named as the present marginal loss (PML), which can be computed using either a more traditional geometric discount or a hyperbolic approach that penalizes less the long terms benefits (over 50 years) achieved by the recovery of the natural ecosystem (e.g., forest), as proposed by Roman et al. (2012)[24]:

where ML is the marginal loss (difference of value between pre and post-fire conditions), r is the discount rate (set by Roman et al. to 2%, but suggested to be between 1% and 3% to better reflect the social temporal preferences of society [25] rather than private market conditions — 5 to 10%), and nb is the estimated recovery time of the particular ES being assessed. PML should be added to the actual ML to estimate the total loss.

However, it should also be pointed out that the use of monetary valuation has been controversial for decades [26] [27] [28], and many alternative methods exist to account for the multiplicity of ES components and their trade-offs. A recent review of existing methods for the valuation of nature by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (approved by 139 countries) [29] [30] indicated that in less than 20% of the studies dealing with the quantification of ecosystem services, a common unit was used, and monetary units were used in a subset of these studies.

Return to Conceptual Framework Diagram

¶ References

Bateman, I., & Mace, G. (2020). The natural capital framework for sustainable, efficient and equitable decision making. Nature Sustainability, 3, 776-783. ↩︎ ↩︎

Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S.J., Kubiszewski, I., Farber, S., & Turner, R.K. (2014). Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 26, 152-158. ↩︎

La Notte, A., Vallecillo, S., Garcia Bendito, E., Grammatikopoulou, I., Czucz, B., Ferrini, S., Grizzetti, B., Rega, C., Herrando, S., & Villero, D. (2021). Ecosystem Services Accounting: Part III-Pilot accounts for habitat and species maintenance, on-site soil retention and water purification. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Commission. ↩︎ ↩︎

Vallejo-Villalta, I., Rodríguez-Navas, E., & Márquez-Pérez, J. (2019). Mapping Forest Fire Risk at a Local Scale—A Case Study in Andalusia (Spain). Environments, 6, 30. ↩︎

Molina-Martínez, J.R., Herrera, M.A., & Rodríguez y Silva, F. (2019). Wildfire-induced reduction in the carbon storage of Mediterranean ecosystems: An application to brush and forest fires impacts assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 76, 88-97. ↩︎

Molina-Martínez, J.R., Zamora, R., & Rodríguez y Silva, F. (2019). The role of flagship species in the economic valuation of wildfire impacts: An application to two Mediterranean protected areas. Science of the Total Environment, 675, 520-530. ↩︎

Faith, D.P. (2021). Valuation and appreciation of biodiversity: The “maintenance of options” provided by the variety of life. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 635670. ↩︎

Sil, Ã.n., Fernandes, P.M., Rodrigues, A.P., Alonso, J.M., Honrado, J.o.P., Perera, A., & Azevedo, J.o.C. (2019). Farmland abandonment decreases the fire regulation capacity and the fire protection ecosystem service in mountain landscapes. Ecosystem Services, 36, 1-1. ↩︎

Martino, S., Roberts, M., Stevenson, T., Ovando, P., Mouillot , F., Pernice, U., Ortega, M., Velea, R., Laterza, R., & Moreira, B. (2022). Developing an Integrated Capitals Approach to Understanding Wildfire Vulnerability: Preliminary Considerations from a Literature Review. In D.X. Viegas, & L.M. Ribeiro (Eds.), IX International Conference on Forest Fire Research (pp. 1073-1083). Coimbra, Portugal. ↩︎

Pearce, D.W., & Turner, R.K. (1990). Economics of natural resources and the environment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩︎

Turner, R., Badura, T., & Ferrini, S. (2019). Valuation, Natural Capital Accounting and Decision-Support Systems: Process, Tools and Methods. ↩︎

Potschin, M.B., & Haines-Young, R.H. (2011). Ecosystem services: Exploring a geographical perspective. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 35, 575-594. ↩︎

Molina-Martínez, J.R., González-Cabán, A., & Rodríguez y Silva, F. (2019). Wildfires impact on the economic susceptibility of recreation activities: Application in a Mediterranean protected area. Journal of Environmental Management, 245, 454-463. ↩︎ ↩︎

Valatin, G. (2014). Carbon Valuation in Forestry and Prospects for European Harmonisation. EFI technical report 97 ↩︎

Boxall, P.C., & Englin, J.E. (2008). Fire and Recreational Values in Fire-Prone Forests: Exploring an Intertemporal Amenity Function Using Pooled RP-SP Data. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 33, 1-15. ↩︎ ↩︎

Abiodun, A.A. (1978). The economic implications of remote sensing from space for the developing countries. In, Earth Observation from Space and Management of Planetary Resources (pp. 575-584). Paris: ESA SP-134. ↩︎

Loomis, J., Gonzalez-Caban, A., & Englin, J. (2001). Testing for differential effects of forest fires on hiking and mountain biking demand and benefits. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 508-522. ↩︎

Sánchez, J.J., Baerenklau, K., & González-Cabán, A. (2016). Valuing hypothetical wildfire impacts with a Kuhn–Tucker model of recreation demand. Forest policy and economics, 71, 63-70. ↩︎

Molina-Martínez, J.R., Moreno, R., Castillo, M., & Rodríguez y Silva, F. (2018). Economic susceptibility of fire-prone landscapes in natural protected areas of the southern Andean Range. The Science of the Total Environment, 619-620, 1557-1565. ↩︎ ↩︎

Thompson, M.P., Calkin, D.E., Finney, M.A., Ager, A.A., & Gilbertson-Day, J.W. (2011). Integrated national-scale assessment of wildfire risk to human and ecological values. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 25, 761–780. ↩︎ ↩︎

Molina-Martínez, J.R., Rodríguez-Silva, F., & Machuca, M. (2017). Economic vulnerability of fire-prone landscapes in protected natural areas: application in a Mediterranean Natural Park. European Journal of Forest Research, 136. ↩︎

Varela, E., Jacobsen, J.B., & Mavsar, R. (2017). Social demand for multiple benefits provided by Aleppo pine forest management in Catalonia, Spain. Regional Environmental Change, 17, 539-550. ↩︎

Wu, T., & Kim, Y.-S. (2013). Pricing ecosystem resilience in frequent-fire ponderosa pine forests. Forest policy and economics, 27, 8-12. ↩︎

Roman, M.V., Azqueta, D., & Rodrígues, M. (2012). Methodological approach to assess the socio-economic vulnerability to wildfires in Spain. Forest Ecology and Management 294, 158-165. ↩︎

Treasury, H. (2018). The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation. London: OGL Press (www.gov.uk/government/publications). ↩︎

Ackerman, F., & Heinzerling, L. (2002). Pricing the priceless: cost-benefit analysis of environmental protection. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 150, 1553-1584. ↩︎

Baveye, P.C., Baveye, J., & Gowdy, J. (2013). Monetary valuation of ecosystem services: it matters to get the timeline right. Ecological Economics, 95, 231-235. ↩︎

Victor, P.A. (2020). Cents and nonsense: a critical appraisal of the monetary valuation of nature. Ecosystem Services, 42, 101076. ↩︎

IPBES (2022). Methodological Assessment Report on the Diverse Values and Valuation of Nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Bonn, Germany. : IPBES secretariat. ↩︎

Masood, E. (2022). More than dollars: mega-review finds 50 ways to value nature. Nature, d41586-41022-01930-41586. ↩︎